Timber Crash Course

Its actual legacy extends back even further though, into the time before recorded history, when tree-rich rural societies utilised its natural strength, durability, lightweight, and adaptability to build everything: from ships to temples.

The oldest standing timber building in the world is the Horyuji Temple in Japan (above), which is also one of the country’s oldest temples. There is little known about the construction of the temple, but it’s believed the main timber used is cypress wood and that the central pagoda (the oldest part of the temple) was built around the year 600AD, making it over 1400 years old!

For generations, timber has been the natural material of choice, even as more modern materials such as brick, concrete, and steel have taken hold on a wider scale.

This is because timber is not only that much stronger per weight, especially in comparison to steel and concrete, but it is also uncontested as the most environmentally responsible major building material.

The greenest option

Timber has a natural appeal, ages gracefully, and is easily recyclable. Perhaps most importantly, it also acts as a carbon sink when used for building work – naturally locking carbon dioxide.

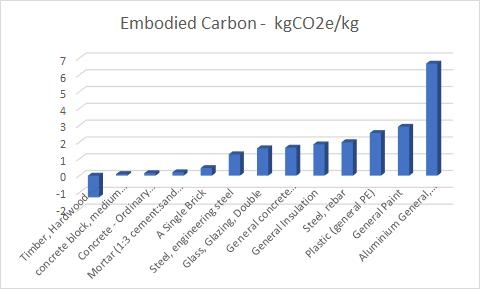

The most respected source of information on embodied carbon is the ICE database, which is freely available. Here are some figures, according to the data collated in the ICE tables:

Since timber is made out of carbon, it can actually have a negative footprint – that is, it stores carbon that it sequestered from the atmosphere and locks it for decades as part of your furniture.

And as long as it is sustainably harvested, timber will continue to be a practically unlimited resource, something no other main building material can claim.

Sustainability

In the 1990s, at about the same time that the importance of sustainable building materials in the modern construction sector grew, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) was set up to save forests and ensure a future supply of sustainable timber, while also protecting its native peoples and fauna.

The FSC logo is a mark that proves a piece of wood or paper has been sourced from a sustainable source and has been risk-assessed against the 10 Principles of Forest Stewardship. It provides assurances that the timber you’re buying comes from (and can be traced back to) forests that follow strict sustainable practices. We wrote more about FSC on this blog here.

Sapwood vs Heartwood

Before we go any further into the intricacies of timber, we first need to understand the different properties of wood found in every tree – sapwood and heartwood. These are the main parts of the tree that make up the “Xylem,” which is the largest part of the tree and sits at the centre. This is the only part of the tree that’s used to produce timber and they each have their own unique attributes.

Heartwood – As the name suggests, the heartwood is drawn from the very centre of the tree and is generally a rich brown or deep red colour and has deeper markings and knots than sapwood. The heartwood is made of old dead sapwood, which provides the structural strength for the tree to grow taller as it reaches for sunlight. Because it is harder and denser, it is also more difficult to treat with chemical preservatives than the sapwood

Sapwood – The next layer, sitting between the heartwood and the bark is the sapwood, which is the living part of the tree.. It’s also a different colour than heartwood, often coming across as brighter, with either white or yellowish hues. Its moisture content is also higher as this is the part of the tree responsible for moving water and nutrients (sap) between the roots and the branches. It is not as durable or resistant to decay as heartwood.

For exterior projects, it is often advisable to use Heartwood only as this is safely more stable and durable than the sapwood part of the tree. However, if your project is internal, there may well be plenty of options to incorporate sapwood into your timber purchase. Most people would be surprised to know that pine, a softwood, has a lot of sapwood, yet still is one of the most widely used species on the planet. So, just because it has sapwood it doesn’t necessarily mean it can’t be used. It’s just that, as all sapIwood is not durable, we resort to treating it with preservative chemicals so it is protected from fungal attack and can be used outside as decking, cladding, fencing and even stakes and posts.

Hardwood or Softwood?

Hardwoods and softwoods can be quite different, with their own distinctive qualities and characteristics so it pays to know when and how to use each type.

In botanical terms, hardwoods come from deciduous trees which lose their leaves annually while softwoods come from conifer trees, which usually remain evergreen. Hardwoods tend to be slower growing, and are therefore usually more dense, hence the name, even though there are exceptions to this rule.

Softwood trees are known as a gymnosperm. Gymnosperms reproduce by forming cones which emit pollen to be spread by the wind to other trees. Pollinated cones form naked seeds which are dropped to the ground or borne on the wind so that new trees can grow elsewhere. Some examples of softwoods include pine, spruce, douglas-fir, cedar and larch.

A hardwood is an angiosperm, a plant that produces seeds with some sort of covering such as a shell or a fruit. Angiosperms usually form flowers to reproduce. Birds and insects attracted to the flowers carry the pollen to other trees and when fertilized form fruits or nuts with seeds. Temperate hardwoods include Oak, Chestnut and Birch while tropical ones are Iroko, Ipe, Mahogany and Ekki.

Softwoods, meanwhile, grow faster and are commonly grown in the more temperate climates of the northern hemisphere.

Although there are notorious exceptions to the rule, hardwoods are usually the denser of the two and tend to be found in more variety in tropical climates, which means they are less common in the UK.

In contrast, hardwoods usually last longer so their environmental and economic costs are mitigated. Still, softwoods are usually more affordable and quite durable, especially when treated, making them the most commonly used timber in construction.

It’s also worth noting that these timbers are typically classified as either “C” or “D” class in terms of their strength. C stands for conifers (softwoods) and D for deciduous ( hardwoods). Strength classes determine how much weight, or load, a board or beam can take before it snaps – or how far it will safely span, such as a floor joist or a roof rafter.

As there are bespoke strength classes for each species of wood, it can be a complicated process to differentiate between, for example, a C24 Pine and a D30 Oak.

Always check span tables and consult an engineer when determining what timber strength class your project requires.

Regarding which wood is more suitable for certain applications, it generally varies from project to project. When used for decking, for example, hardwood is generally longer lasting, with even chemically treated softwood often only lasting for around 15 years when used externally.

Generally speaking, however, cost is the primary factor that most people will fall back on when making their decision. That’s why it’s always important to make a cost benefit analysis, considering your budget, the location of the project, its footprint and what appearance you are looking for before making your decision.

Use Class vs Durability

Alongside their strength, timber species can also be ranked in terms of their durability (measured in years of service) and use class. Use classes are what type of environment the timber will be used in. When it comes to timber selection criteria, durability and use class should play an important role. So, what exactly are the differences between use class and durability? And how does the project environment play into the decision making process?

Durability

Everything decays eventually, the same is true of timber. Durability refers to how long the timber will last in real-world terms, and is generally measured in years. It’s also worth noting that durability will depend largely on the environment in which the timber is being used. Your chest of drawers, for example, could last for centuries in your room, but a lot less if left outside in the rain, wind and sun.

Some timber species are naturally durable and won’t require any additional treatment if they are to be used outdoors, whereas others (and particularly softwoods) will almost certainly require treatment to increase their life service. This is because condensation and humidity harbour fungi and bacteria that break down organic matter such as timber over time. To easily identify how durable a piece of timber is, there are five durability classes, as seen below:-

| Class 1 | Extremely durable (Ekki, Greenheart) |

| Class 2 | Very durable (Chestnut, Cedar) |

| Class 3 | Quite durable (Douglas fir) |

| Class 4 | Slightly durable (Pine, Spruce) |

| Class 5 | Not durable (sapwood) |

Use Class

If durability relates to how long a piece of timber might last, then use class is all about where the timber should be used. Will it be used externally? And if so, will it be kept above ground (such as cladding or a window frame) or kept in regular contact with the ground (fence posts). Or, will it exclusively be used internally (floorboards) and if so, will it be at risk of moisture and damp whether directly or due to condensation?

These are some considerations that go into defining a use class, also split into 5 categories:-

| Class 1 | Useable in dry conditions indoors where exposure to water is highly unlikely |

| Class 2 | Useable in internal conditions where wetting is likely but infrequent. |

| Class 3 | Useable externally, above ground (windows and timber cladding and decking) |

| Class 4 | Useable in external conditions where there is ground contact (fence posts) |

| Class 5 | Useable in water, including salt water (marine sea defence) |

Treatment

Now that you’ve identified what kind of hazard class is your project and the durability class the timber needs to be, you can choose the most suitable type of timber for it.

You may consider naturally durable timbers such as Ekki and Cumaru, or treated softwood, that is timber which has been modified, generally with chemicals, to increase its durability, or life service, for the appropriate use class. There are two main forms of chemical impregnation, which ensure the wood lasts longer without sacrificing its natural properties.

High pressure treatment – Providing anywhere between 15 and 60 years of service life, this treatment is generally used for timber that will be used outdoors (use classes 3, 4 and 5). It involves preservatives being forced deep into the fibres of the wood.

Low pressure treatment – A treatment that is generally used for wood that is going to be used indoors (class 1, 2). It uses a double vacuum process and provides protection against insect and fungi and is an ideal option for protecting construction grade timbers, as it avoids the core of the timber so it manages to retain all of the dimensions and natural moisture of the wood.

Timber in practice

Oak-framed timber buildings have enjoyed something of a renaissance in the UK in recent years due to a general resurgence in popularity when it comes to ‘traditional’ styles. Timber offers a warmth and colour to construction that simply can’t be matched by brick, concrete, and steel. And particularly not by PVC.

Whereas traditional or modern looking, some of the most beautiful and desirable new projects of the last decade have been designed with timber and some of them might surprise you. The 48m long footbridge, for example, which was constructed at the Olympic Park in Stratford, London, is a piece of exceptional engineering. Made from FSC Ekki – one of the most durable species of timber available, it’s a build that will outlast us all.

Indeed, some of the most beautiful projects in the world continue to be timber builds. The Superior Dome in Michigan, for example, is a truly unique work – a 14-story dome spread over 5.1 acres with 781 Douglas Fir beams and 108 miles of decking.

Closer to home, meanwhile, there’s the 9-story Murray Grove in London – a gorgeous apartment complex constructed entirely from timber which its builders say will save 125 tonnes of carbon emissions compared to a concrete structure of similar size.

Timber is the material that continues to defy easy categorisation and will probably still be used as a building material even hundreds or thousands of years from now. For now though, we can supply over 85 species of it and are ready and waiting to help you find the timber that makes your project sing.

Image credits

- Horyuji Temple – z tanuki / CC BY

- The Superior Dome – Bobak Ha’Eri

- Murray Grove in London – Waugh Thistleton Architects / CC BY-SA